A naive model of discursive taste

Taste is eating things

In Taste is Eating Silicon Valley, Anu Atluru makes the argument that technical execution will no longer be a primary differentiator for startups in many domains.

Instead, companies will compete on taste, vibes, feelings, and values: all terrifyingly underspecified concepts for a typical software engineer or technical founder.

The piece is filled with punchy quotes. Here are two:

Code is cheap. Money now chases utility wrapped in taste, function sculpted with beautiful form, and technology framed in artistry.

Founders must become tastemakers, and venture capitalists the arbiters of taste.

Atluru’s case is likely overstated, but it seems directionally correct to me.

AI is getting real good at writing code; this is already dramatically lowering barriers to shipping a lot of software.

The differences between ChatGPT, Claude, and Perplexity are already trending asymptotically towards vibes, values, and brand.

If you’re a technical founder who tends to outsource core aesthetic workflows to designers and brand agencies, it’s probably time to think about growing some aesthetic chops of your own.

Acquiring taste

If the future belongs to designers and creatives with good taste, then what are we neckbeard backend engineers supposed to do?

How do we develop a sense of taste in a domain?

I see two primary approaches: we can make things, and we can learn to form opinions about things. These map, roughly, to being an artist and being a critic.

The critic develops and performs taste without necessarily making concrete artifacts. We might call this discursive taste.

Of course, the artist also forms opinions and perspectives. These opinions often incite the act of creation itself. And the act of trying to make a thing is perhaps the most direct tastemaking practice that exists. Putting a thing in the world is a forcing function for developing aesthetic skills and making hard choices.

But making things tends to involve a set of domain-specific technical skills. Discursive taste is knowledge- and experience- intensive, and I think we can make some claims about developing it that generalize across different domains. So I’ll focus on critical taste here.

Taste is eating things (and being able to talk about the things you eat)

We should think of discursive taste as a kind of subject matter expertise. It is trainable, developable, entirely learnable.

What are its primitives?

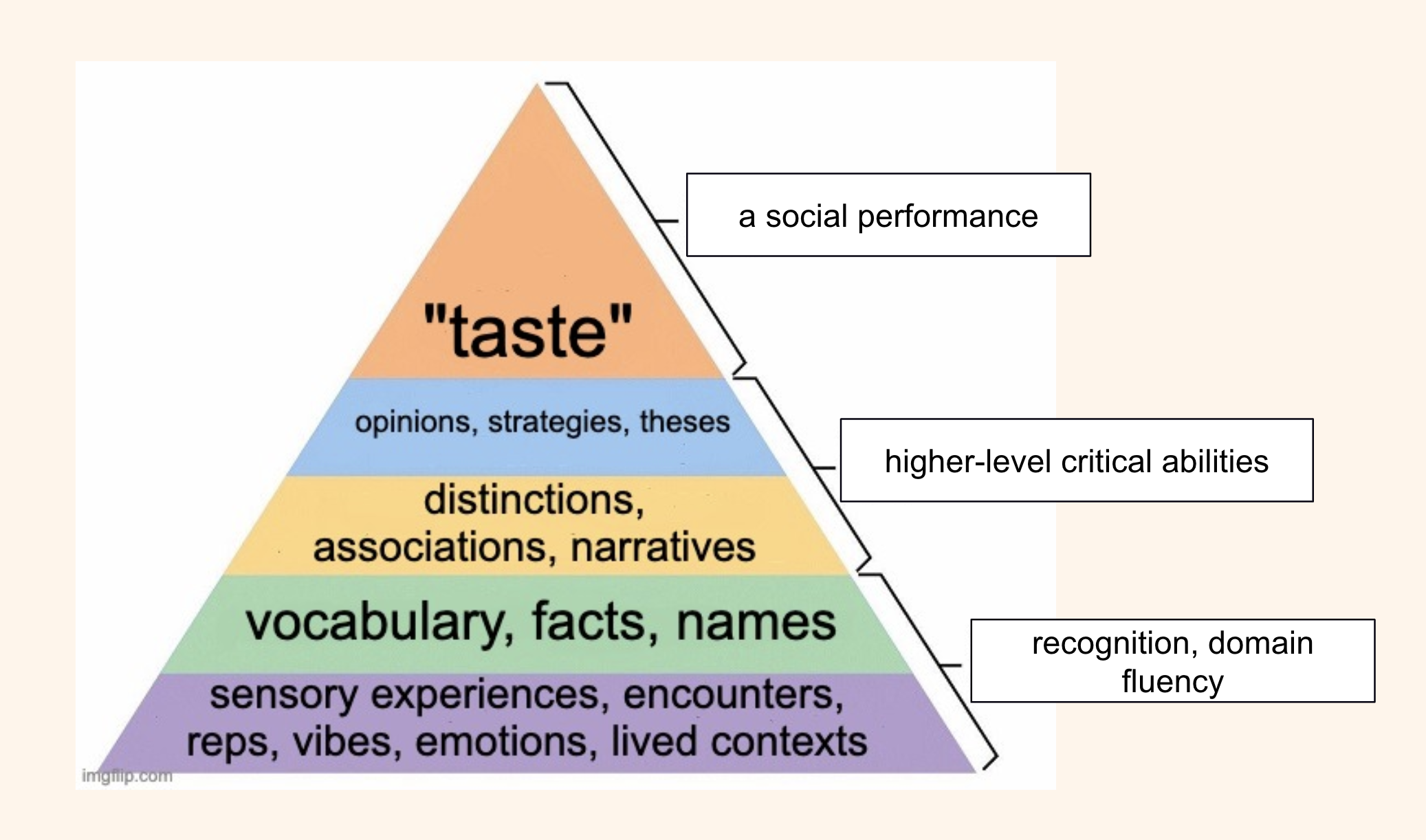

Below is a WIP, empirically unsubstantiated, under-researched model of the building blocks of discursive taste:

Recognition skills and basic domain fluency

It’s worth stating the obvious: if you want to have good taste in a domain, you need to form opinions about concrete elements of that domain. In order to feel confident doing that, you likely need to have encountered a nontrivial amount of the stuff that makes up the domain. You need to feel a sense of familiarity.

We’re talking volume. Reps. Breadth. Taste is eating things - lots of things.

But it’s not enough just to have experienced a broad swathe of elements in a domain. I frequently throw on one of the 5 classic jazz albums I know about and let Spotify take the reins when the album ends. I may be encountering a decent spread of artists when I do this, but I’m not improving my discursive skills.

If you want to be able to talk about stuff, you need specific words, concepts, names, and facts.

You have to be able to name things and describe them using domain-specific vocabulary. To classify them according to relevant taxonomies.

You have to become a bit like Shazam, or an object detection model.

This is knowing a mare from a mule; telling a hawk from a handsaw.

People who grow a sense of taste organically over a long period of time often develop these recognition skills implicitly through immersion.

Many might balk at the idea that you can explicitly train these skills via tools like spaced repetition and products like recognition games.

But I suspect one can shortcut the acquisition of basic discursive fluency in most aesthetic domains, whether it’s visual art, or jazz, or typography, or 10 years of B2B SAAS brand identities for a given vertical.

Higher level critical abilities

Broad, low level recognition skills and basic vocabulary are of course not sufficient to form a sense of taste.

But they are the stuff on which higher order discursive skills are built, like: making associations, telling stories, drawing distinctions, and confidently communicating in abstractions and generalizations.

To develop these skills, it helps to go deep on domain elements that pique your curiosity. We’re talking books or essays on specific artists; consuming entire discographies; learning some history.

Watch this space for more ideas on developing this tier of capacities.

Opinions, strategies

Here we deploy higher level critical abilities in a social context. We put them to use.

What’s missing?

Some things that might be missing:

- Writing. The critic’s primary outputs are writing.

- Social acts of tastemaking: recommending, posting, debating, etc.

- Intuition, hunch, gut. Where does this belong?

- Preference formation

- Techniques that creatives use to gather inspiration

- Practices of curation

- Lists

- Mood boards

- Arena

- An intuition about popularity; having a feel for domain elements that occur frequently versus infrequently; claiming things to be “niche” or “standard”